Home » Articles posted by Frances Smith Starn

Author Archives: Frances Smith Starn

I WANT YOU TO DO SOMETHING, SHE SAID

“I WANT YOU TO DO SOMETHING,” SHE SAID

Once Upon a Time in Kandahar

In the southern city of Kandahar, after long years of bloody war, a royal proclamation forbade the taking of life from humans, and all other animals as well.

“. . . hunters and fishermen have given up hunting. And those who were intemperate have put a stop to their intemperance according to their ability and [become] obedient to their father and mother and elders, unlike the past. And in the future, they will live better and more happily, by acting in this manner at all times.”

Inscribed in Greek and Aramaic on a rock in Kandahar in 260 B.C.E., the imperial edict was broadcast as far as north Africa and the eastern Mediterranean.

The singular peace may have lasted until the death of its author, the emperor Ashoka, in 232 B.C.E. The Kandahar Edicts–thirteen or fourteen in all–were still legible when found in the 20th century. A cast of the peace proclamation is in the Kabul museum in the unlikely event that you are planning a trip to Afghanistan.

In another familiar scene of recent imperial devastation, in southern Iraq, excavation has begun on the site of a 4,000 year-old city in the middle of a desert known as the “Fertile Crescent,” which sustained ancient Mesopotamian civilizations.

The Tigris and Euphrates were the first rivers used for large-scale irrigation, beginning about 7500 years ago. The first water war was also recorded here, when the king of Umma cut the banks of irrigation canals alongside the Euphrates dug by his neighbor, the king of Girsu.

In recent years,Turkey’s damming of the Euphrates threatens parts of Syria and drought-parched Iraq. International conferences have been convened to deal with the crisis, to increase release of dammed water to flow downstream.

California, where I live, is normally dry and now, besieged by climate change, with persistent drought and rampant wildfires. Farmers and agronomists are testing drought-resistant strains of olives, vines, almonds and pistachios from the Middle East. California’s own fertile delta has always been heavily dependent on declining snow runoff from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, and on government subsidies.

Dams and water supply are a flammable issue everywhere, in California as well as the Middle East. In Syria, drought was recognized late as a major cause of their ongoing civil war. Bashar al Assad might have maintained a precarious and even ecumenical peace, but drought in 2006-9 brought crop failures and hordes of youth without work.

In October 2010 I was traveling through the Syrian desert, passing through Palmyra’s storied ruins, toward the eastern border with Iraq. At the town of Deir Ezzor the suspension bridge leading across the Euphrates to Iraq was lined with youths on display, evidently selling themselves. Farther down the Euphrates, we visited the ancient sites of Dura Europus and Mari. In the course of the war, they were looted, and the suspension bridge, built by another imperial power, in this case the French, was destroyed by Assad’s army.

Back to Afghanistan, where the latest atrocity in the U.S. withdrawal involved a poorly judged drone attack which killed ten members of the family of an Afghan aid worker. Seven were children. There were no U.S. casualties, and President Biden has assured us that U.S. troop withdrawal is being replaced by “over the horizon” warfare–of which that drone attack is only one sample.

Breaking news which may not outlive one or two news cycles: U.S. forces evacuating Afghanistan are not going home; they are shipping out to Iraq.Meanwhile, massive mosque bombings in Kunduz and Kandahar continue, even without western intervention, the sectarian violence of Sunni against Shiites. But also without western intervention, Afghanistan and Iran have finally reached an agreement on the water rights for the Helmand River.

Amid the long rotations of civilization and destruction in Kandahar, there was that one early ruler who called for an end to all killing. Ashoka was surely less benign than the Kandahar Edict suggests. Yet after a violent close to the latest imperial occupation of Afghanistan, the ancient king’s vision of peace seems restorative. And somehow the ancient rivers still curve through the dunes and the fields, and humans still struggle for the land and for a share of the life-giving waters.

∞People’s Park UPDATE, Berkeley, July 2025

In Berkeley, at Harvard, Columbia—any American universities whose administrations are not brain-dead—everyone fears Trump’s next move. Among his thwarted peacemaking efforts and his tariff games, he will do what he can to destroy an educational elite who questions his MAGA pretensions.

Two years ago, I checked occasionally on the encampment in People’s Park just a block and a half from my house. A smoky haze almost hid the new red tent that appeared that morning, and the university campanile and its celebrity falcons were obscured behind the scrubby trees. Upwards of twenty tents were scattered through the park.

Fifty years ago, two blocks of old houses like mine were demolished for student dorms that were never built. In time the space became a parking lot, morphing into People’s Park, a famous forum for antiwar protests, drugs, and what remained of Sixties counterculture. Over time the park devolved into a homeless camp, whose few inhabitants had little energy for coherent political rebellion.

Tent camps are both the oldest and the latest response to California’s housing crisis. Gavin Newsom’s optimistic program, Project Roomkey, placing vulnerable unhoused in vacant hotels and motels, was only tenable with federal support. What seem to be working, still and again, are these tent communities, whether scattered and scruffy or–not often–in neat grids, with services. Homelessness in this affluent society is hardly a new phenomenon. What is new is the emergence of these encampments in city centers and at highway intersections, where their high visibility and persistence painfully signal, any way you look at it, a broken social contract.

The founding myth of the University of California describes eminent clergy shading their eyes as they gaze across the bay, quoting Bishop Berkeley: “Westward the course of empire….” More recently, the University has been described as a group of entrepreneurs seeking a parking place.

In 1868, joking aside, the location of the new university campus vastly inflated the property values of four local investors. Francis Shattuck, William Hillegass, and their partners had divided a square mile of land just south of the projected campus, for which they had paid about $31 per acre. The loser in this deal was ultimately the holder of the Mexican land grant, Jose Domingo Peralta–not counting the few surviving natives, whose history is piously noted in historical plaques and

Francis Shattuck’s eventual heir was philanthropist Weston Havens, a childhood friend of the maiden lady who sold us her family home. When we moved in, he gifted us with sacks of fertilizer meant to sustain the viciously rampant Silver Moon rose over the driveway trellis. He wanted to soften the view of the four-story apartment building south of us.

Meanwhile, our clapboard manse on Hillegass was continuing to increase in value as the Bay Area economy boomed. A century past the Gold Rush, there was the pulsating prosperity of Silicon Valley and its garage geniuses. And in California, especially, the rich grew richer, billion by billion, and the poor poorer, year by year, decade after decade.

As Henry George, 19th-century economist and social reformer, observed: . . . the tendency of what we call material progress is in nowise to improve the condition of the lowest class in the essentials of healthy, happy human life. George saw the root cause of inequality as wealth increasing through unearned land value, whether near the new transnational railroad lines or next to the projected campus of what would soon become the world’s top public university. Henry George’s solution, a single tax on land value, soon proved flawed, since land’s value also depends on its potential and its improvements. In 1880 George left the west coast to try out his progressive ideas in New York City. In the mayoral race, he finished well ahead of Republican Theodore Roosevelt, but lost narrowly to a Democratic candidate whose name I and many others have forgotten. * *

Real estate profiteering, hard to regulate, remains a prime cause of homelessness. A group of homeless mothers in Oakland, California recently defeated eviction efforts by a major speculator and gave a boost to community land trusts

* *

While property tax remains the main source of funding public services. California voters have repeatedly rejected any tax increases, even on the fattest commercial and industrial property. As the state budget shrinks support for public schools and colleges, the University of California, already short of housing, raises tuition costs and expands enrollment to fund its programs. And builds on a historic site of protests against our misguided wars.

Antioch–Tales of Two Cities

Now that impeachment has slid off the table into history, and the Capitol attack boasts an ongoing commission, we return to Topic A, the pandemic. Everyone agrees that the shameful disorder of our government and economy–and now even the wintry weather–made a shambles of the vaccine roll-outs. Angry citizens claim to be deprived of access to vaccine, while others are faulted for rejecting it.

Our best vaccination option was some thirty miles away in a town we had never had reason to visit.

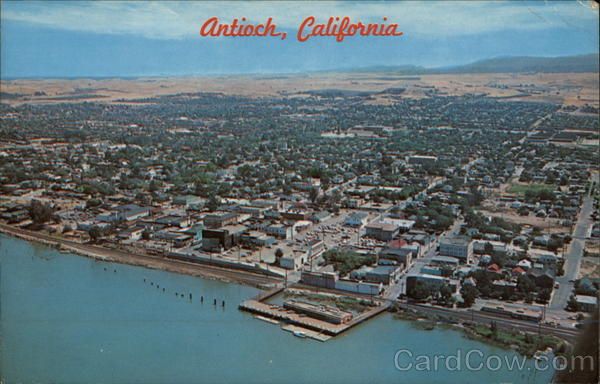

In Antioch, California, the January sun was warm, and people, mostly men with hard hats, were eating lunch on concrete benches in the middle of a parking lot. Sutter Health Foundation anchors a modest medical mall with fueling stations such as Xtreme Burger, Subway, and Starbucks. We found an empty bench and ate burgers prepared by one small, efficient Asian man who seemed to be working alone. Unemployment in Antioch is upwards of 10 percent, highest in Contra Costa County. This figure was not available on the City of Antioch’s website, which features a photo of a dapper administrator flanked by an eye-catching but empty template.

Sutter Health is the second largest employer in town. We passed through its glass portal to meet a receiving line of beaming young women who serially confirmed our identity and body temperature. The ratio of attendants to patients seemed about six to one. An attendant led us toward a receding corridor lined with additional young persons in pastel scrubs, smiling reassuringly as we passed. Magic Flute came to mind. In the room at the end of the corridor stood Krystelle, tall and lovely, with a crown of magnificent braids–and the vaccine. The jabs were painless, followed by a friendly question: had we been able to see anything much around Antioch? “In the summer, you can visit some sweet wineries in Brentwood,” she said.

In fact we had arrived early, in time for a quick turn around the town and the waterfront. Near the river, a sign on a small weathered building said Vets Help Lunch and Medications. Around the corner at the Antioch Community Center, a long line, including several wheelchairs, was also moving slowly toward vaccinations. Down the road at the deserted marina, there were no boats on the river, which had once been the main shipping channel of the San Joaquin-Sacramento river route to San Francisco Bay.

Antioch had begun as Marsh Landing, after John Marsh (Harvard, 1823), one of the early American pioneer entrepreneurs. Marsh had made his way west as an Indian agent, merchant, doctor, and finally, rancher and real estate speculator. During his time in the pueblo of Los Angeles, he was the only “western-trained” medical doctor around, thanks to the illegible Latin of his Harvard diploma. Having saved a tidy amount in in-kind medical fees, he liquidated his inventory and went north.

For $500 (or $300, depending on your source) Marsh became the owner of the 13,000-acre Rancho Los Meganos, a cattle ranch east of San Francisco Bay. He soon became a promoter of the joys of California life, writing widely circulated letters to encourage emigration, statehood, and of course the purchase of homesteads on his property. This land he had acquired from the Mexican government, via Spain, which had first dibs, unless you count those indigenous tribes. The history of California as a continuing land grab is not unknown, beginning with the Franciscan missions and Indian slave labor.

For his part, John Marsh sold a piece of his river property to the Smith brothers, bearded twins unrelated either to the cough drop dynasty or my family. William Smith, a minister, wanted to give the town a biblical name. He must have known his history to have chosen the ancient Greek “Antioch,” another town located at a delta formed by two major rivers.

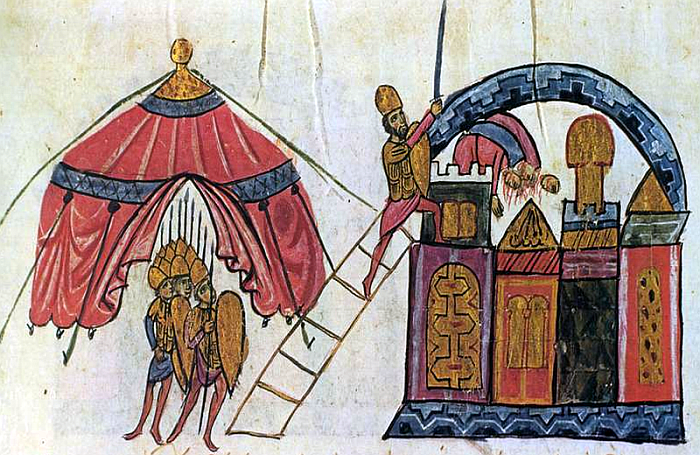

The original Antioch was founded by a general of Alexander the Great, near a delta of rivers opening onto the northeastern Mediterranean. It became a center of commerce and culture during the Hellenistic and Roman empires and beyond. It was also a religious center where the followers of Christ, including Peter and Paul, were first known as Christians. This history as well as its riches made it a target of the First Crusade.

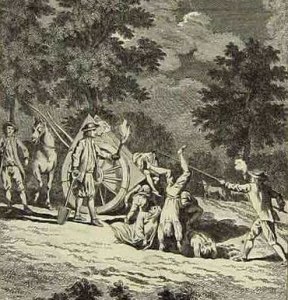

Fall of Antioch in 1098, earlier version

Ancient Antioch is now only ruins in the Turkish town of Antakya near the Syrian border. Just south of that border, in the Syrian province of Idlib, nearly everything is in ruins, both ancient and recent. In the years before the Syrian civil war, Idlib province was mainly known for the “Dead Cities,” hundreds of Byzantine settlements from the first through seventh centuries, preserved when trade routes changed.

Antiochus III the Great expanded the Seleucid empire in the usual way, through conquests and prudent marriages, and lost it in the usual way, by decisive military defeats–in his case as in so many others, by the Romans. But today, if the facts were more generally known, Antiochus would probably be more famous for being the father of Cleopatra than for Thermopylae. Reflections on the transient glory of military conflicts tend to attract less interest over the centuries than tales of sex, incest and violence like Cleopatra’s—and some much more recent.

In 2009 Antioch, California became suddenly notorious with the discovery of a kidnapped girl who had been kept there in captivity for 18 years. International media feasted on the story of Antioch’s alleged 1,000 registered sex offenders in residence, with domestic variations on the theme from Anderson Cooper, Larry King, Diane Sawyer, Oprah, and Judge Judy. Jaycee Dugard received $20 million from the state of California, acknowledging defective law enforcement. She wrote a best-selling memoir and established a foundation to support other victims of rape and kidnapping.

Ten years after the Jaycee’s rescue, the streets of Antioch seem calm, but police blotters tell another story. In one week in February there were 48 adult arrests, including the alleged shooter of a firefighter and paramedic, as well as a lunchtime bank robbery the day before our vaccination visit.

The streets are lined mainly with working-class cottages and no-frills condominiums, but with California property inflation, the median house price is now $540K, affordable mainly for desperate commuters employed in the central Bay Area.

John Marsh got the 13,316 acres of Rancho los Meganos for the equivalent of about $3.75 an acre in 1850 dollars. California’s legislature never ceases to recognize the need for affordable housing, but voters are no more inclined to tax raises than John Marsh would have been.

On our way to vaccination in Antioch, California, we could see from the highway a green spread of regularly distributed bumps and cubes over many acres. It looks like, and is, camouflaged weapons storage, now, we are told, empty. After the horrendous Port Chicago disaster in July 1944, when thousands of pounds of naval ordnance exploded during loading, killing 320 and wounding 390 mostly black Americans, a new name and new uses were proposed for the site.

For a while it was the proving grounds for testing self-driving cars, most notably Mercedes Benz. Then in 2018 the Navy floated a plan to build a tent city there. As many as 47,000 immigrants could be detained on this somewhat toxic but isolated Superfund site. Local protests resulted, and Congressman Mark DeSaulnier, who called the plan “madness,” assured his constituents that the projected tent settlement would not be built. The Navy continues to work on decontamination in hopes of making the land salable for residential or park development.

Some twenty minutes from the erstwhile naval weapons station, Marsh Creek State Historic Park now incorporates much of the former Rancho Los Meganos and the Marsh Home. John Marsh had lived alone in his adobe hacienda for decades, but for his new wife he planned a fairly grand stone manor with a tower to spy out cattle rustlers.

Construction was still underway when his wife died, and not long thereafter he was murdered by his own vaqueros after a wage dispute. “The meanest man I ever knew,” said John Bidwell, another early California pioneer.

The Marsh Creek State Park may reopen after the pandemic, but it appears that the house may be allowed to fall into ruin. And who will take responsibility for the hundreds of human burials discovered nearby, dating from 3,000 to 4,000 years ago–long before Antiochus the Great and his daughter sat uneasily on their respective thrones.

In the ruins of ancient Antioch, in 1932, a consortium of American and European museums found a trove of magnificent Byzantine mosaics. Their excavations were interrupted in 1939 by the war. Half of the mosaics were immediately absorbed by the excavators’ home museums. The others were left to Antakya, and we can only hope that they are no longer on display in the Hatay Archaeological Museum, less than 90 kilometers from Idlib in the heart of Syria’s northeastern war zone.

Restoration in America and Elsewhere

Braced for the latest of Trump’s parting outrages, we can only speculate about Joe Biden’s prospects of restoring America’s mutilated democracy. A literal restoration unfolds daily as Obama-era survivors surface for Cabinet-level jobs. Some are Biden intimates with deep government experience, while others fill quotas of ethnicity and gender.

Of course the carping has commenced: is “Build Back Better” all that reassuring? It was used earlier in disasters in Haiti and the Philippines, and later by Boris Johnson, about Brexit.

Arguably the most renowned political restoration in western history was that of the English king Charles II, in 1660. Following his father’s beheading, he had spent much of his exile in France while his boy cousin, Louis XIV, was working on becoming the Sun King.

In England, Charles became known as the “Merry Monarch”, and sometimes as “Old Rowley”, a renowned breeding stallion. After the harsh strictures of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan regime, Charles’s pleasure-seeking ways prompted the rise of racy, witty Restoration comedy.

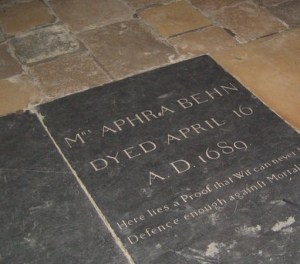

One of the most popular of the Restoration playwrights was Aphra Behn, cited by Virginia Woolf as the first Englishwoman to make a living as a writer. We know little of her life, but she seems to have turned to writing after a failed career as a spy for her king in the Dutch court. Although Charles evidently neglected to pay for her services, she remained a Royalist and composed nasty screeds against the Opposition Whigs.

Years before Charles II fled to England, Aphra Behn died, seemingly of natural causes, and was buried, rather remarkably, in Westminster Abbey. (Proof that neither Wit  nor Embonpoint are defense enough against Mortality.)

nor Embonpoint are defense enough against Mortality.)

Charles was unlucky enough to reign during the Great Plague of London in 1665, which overlapped the Great Fire in 1666.The pestilence began in the spring, and by July those who could fled the city. The king and his family and court took refuge in Oxford, where Parliament and courts soon set up for the interim.

Charles published a proper royal proclamation with extensive public health orders intended to minimize the spread of the infection—more than Trump did 355 years later. Nonetheless, an estimated 100,000, one fifth of the population, died within 18 months. Mass burials have been unearthed in so-called plague pits around the city–the latest London tourist attraction.

Hardly was the ground settled on the graves when the Great Fire engulfed the city in a mere three days of September 1666.

The Great Fire broke out at the end of the hot, dry summer of 1666, and consumed much of the City of London, including the homes of 70,000 of 80,000 citizens. A deranged French watchmaker claimed to have started the blaze and was hanged. Catholics were also blamed, the Dutch, and any stray foreigners. Eventually it was agreed that the fire had originated in the kitchen of a bakery in Pudding Lane near the river. Can we trust a source that claims King Charles and his brother joined and directed fire-fighting efforts?

Afterwards, in any event, Charles did work to restore London culture, sponsoring the Royal Society and founding the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.But all was not well at court. Although Charles had a dozen offspring from various mistresses, his queen had produced no heirs. Catherine managed to keep her head and her place in court, but the stage was set for the Second Restoration, that of Charles’s brother James. Then James II too was forced into exile in France when the parliament of the Glorious Revolution invited William of Orange and Mary Stuart to occupy the English throne.

While royal fugitives from the British isles had always found comfortable exile across the channel, the post-revolutionary French had multiple restorations of their own, mainly within the House of Bourbon. After Napoleon fled to Elba, there was Louis XVIII, brother of Louis XVI, who had ended so badly.

“The Bourbons have learned nothing and have forgotten nothing,” said Prince Talleyrand. We could take a moment to compare Talleyrand, that shrewd and unscrupulous advisor to frivolous kings, to Antony Blinken, Biden’s head diplomat. Briefly, both were educated in France. We could take another moment to compare Joseph Robinette Biden to Charles Stuart, king of England, et al. But tempus fugit.

An appetite for royal restoration still survives in Central Europe. The Monarchist Party of Bohemia, Moravia & Silesia marched just last year in support of the return of Habsburg rule over themselves and several other Central European republics. The heir to this ancient dynasty would be Karl von Habsburg, archduke of Austria and royal prince of Hungary, Bohemia, and Croatia, whose resume’ includes pertinent service in the field of cultural preservation.

Architectural preservation–and restoration, even more–is often politically controversial. In Germany, long after the carpet bombing of World War II, there is now the Neue Altstadt, New Old Town, quaint and costly at a time when the great need is for affordable housing. And there is the recent reconstruction of the Berlin City Palace, not to mention the Potsdam Garrison church, built by Frederick II, visited by Bach, Czar Alexander, and Napoleon–and where the German parliament met for Hitler and Hindenburg’s handshake after the Nazi victory in 1933.

After the war, the thriving United States economy could support major rebuilding of Europe with the Marshall Plan. The U.S. was producing half of the world’s GDP. Now, what with one thing and another, it’s down to one-seventh. Yet Biden talks of restoring American “leadership”. Biden and Harris were elected to return us to “normal”, which includes our traditional political patronage system supporting our vast military industrial complex and our famously hypocritical foreign policy.

The U.S. does still lead the world in one area: arms production and trade. Decades ago we found a way to help Saudi Arabia spend its petrodollars while improving the U.S. balance of trade; each year we sell them millions of dollars’ worth of U.S weaponry, including fuel and servicing. These are currently being used most effectively against civilians in the Saudi proxy war in Yemen.

But starting and ending military and trade wars, breaking or blocking treaties and agreements, may now proceed without reference to the price of a barrel of oil or to a late-night tweet from Trump.

Much could depend on the restoration of a working majority in the Senate through election of two Democrats in Georgia. All of the resources of both parties (mine, plus dark money to buy votes and/or poisonous TV ads) are engaged in this epic struggle–except for those funds needed to pursue Trump’s continuing campaign to invalidate the presidential election.

But our new president and Congress can make significant moves with or without a Congressional majority. Some actions are automatic and symbolic, such as returning to the Paris Climate accords. Others are material and obvious, such as retracting the $500 million in arms pledged to Saudi Arabia. The Internal Revenue Service could be expanded and improved without special legislation to reinforce collection of billions in corporate taxes. Aside from its economic justice, the revenue would help pay for new public works projects to repair infrastructure, build affordable housing, and construct national grids for renewable energy and universal internet. Collateral benefit: full employment. (This last might be seen as an echo if not a restoration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s WPA in the 1930s….but hasten the day!)

With the Georgia election, looming protest in our capital, and a surging pandemic, we still have room to worry on a cosmic scale. Worst case: a Trump Restoration in 2024…if not Donald, then Ivanka.

*The idea of Build Back Better, as it was proposed in 2015 by the Japanese at a UN conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, was to restore local infrastructure, culture and environment to what they were before the natural disaster that disrupted them. Only substitute Donald Trump for “natural disaster” and the same dictum, BBB, obtains.

Consider the Crow

While crows in increasing numbers crowd smoky Bay Area skies, humans think of migrating to more hospitable climes. Crows, handsome and black, loud and smart, line up on electrical wires above us or linger in the middle of the street to finish a scavenged snack. Are they attracted by the spread of homeless settlements with those exposed middens so repellent to the tidily housed?

Cities are perhaps safer now for crows than fields protected not only by scarecrows, but farmers with real guns, and enthusiastic hunters. Here the young daughter of an “NRA family” has scored her first crow kill. It seems safe to say that her parents will remain Trump voters, although Wayne LaPierre and the NRA, as well as the Republican Party, are in disarray.

Cities are perhaps safer now for crows than fields protected not only by scarecrows, but farmers with real guns, and enthusiastic hunters. Here the young daughter of an “NRA family” has scored her first crow kill. It seems safe to say that her parents will remain Trump voters, although Wayne LaPierre and the NRA, as well as the Republican Party, are in disarray.

Crows, science has recently informed us, are not only crafty, but possess conscious awareness. I.e. they know what they know–which is more than can be said for many humans. Crows mate for life, although according to one source they are only “monogamish” and like a bit on the side now and then. Young crows, instead of looking to start a new family, hang around their old nest for a couple of years and help out with the chicks. Whether that is also typical of human adolescents is debatable.

We planted some redwoods–such lovely trees– between us and the student apartments next door. “Madness,” said a friend who knew California as only a midwestern native could. “They are just giant weeds.” Years later, as redwood roots grew intimate with the neighbors’ plumbing as well as ours, the redwoods were taken over by two nests, one crows’, one squirrels’. In the spring we sometimes heard squirrely sounds of rutting, but more often it was hard to distinguish the angry scolding of a squirrel from the assertive cawing of a crow. All of them fled during the traumatic tree work, but they seem to be returning, if only to check out the new perch of the plaster seagull above the porch.

Crows used to come uninvited to meet a few of our friends sharing distanced drinks and close-in anxieties on our pandemic terrace. Covid corvids were more likely to appear when shrimp or smoked salmon was on offer. And they seemed to be more interested in our older friends…as are we, often enough.

One summer when my mother was recovering from serious surgery, crows collected on her redwood deck in the warm Los Gatos afternoon–not, I supposed, to wish her well. I chased them away with blasts from the garden hose. Watering her garden, daily and plentifully, was an important strategy in her plan for eternal life. During a year when we were living in Italy, she took me to Venice for my birthday. On the Riva degli Schiavoni the traditional souvenirs were all arrayed: glass from Murano and China, gondolier’s hats, masks of all descriptions.

The Venetian tradition of masks is much older than Carnival, with their earliest regulation recorded in the 12th century. They were worn commonly by the prosperous and somewhat amoral citizenry, who might prefer to conceal their financial and amorous adventures. Four hundred noble families were rich and aristocratic enough to lead a life of fairly unrestrained pleasure. The families included various dissipated relatives, but not of course the enabling household servants–who sometimes benefited from hiding their own identity behind masks, as we learn from Mozart operas.

In the 1530s the master mask-makers’ guild had eleven busy members, including one Barbara Scharpetta. The decadent life of the Venetian aristocracy continued until the end of the Republic in 1797. Masks were then forbidden altogether, and Carnival itself was not resumed until 1979.

In the time of the Black Death, the curved beaks of Venetian plague doctor masks were filled with dried flowers, herbs and spices, or camphor. The mask was worn to keep away foul smells, known as miasma, that were thought to transmit the plague.

Miasma had been regarded as the main cause of disease as far back as ancient China. A Chinese poet of the Tang dynasty, Han Yu, was sent into exile. (Poets in ancient China were more politically significant than in 21st-century America.) In the unhealthy southern province, expecting to die, the poet wrote: I know that you will come from afar. . .and lovingly gather my bones, on the banks of that plague-stricken river.

From miasma came malaria (literally “bad air”) in medieval Italian. Though miasma is mainly associated with the spread of contagious diseases, early in the 19th century the theory went rogue, suggesting, for example, that one could become obese by merely inhaling the odor of food.

Even after scientists and physicians realized that specific germs, not miasma, caused specific diseases, getting rid of odor through underground sewage systems and garbage cleanup in urban ghettos became a high priority for city governments. The observed connection between foul air, poor sanitation and disease lasted until the mid-nineteenth century and beyond. Plague doctor masks, however, are still available in any Venetian kiosk. Do we have even now a more useful term than miasma to explain the spread of our latest pandemic? Or any protection more effective than vaccine, and masks?

Five hundred years after the Black Plague, crows were still keeping bad company. In the 1830s, “Jim Crow” was a kind of dancing jester created by a popular white minstrel singer, wearing blackface. “Jim Crow” came to refer to the many forms of segregation and injustice toward African- Americans that followed Reconstruction after the American Civil War and far beyond.

In World War II, “Old Crow,” mostly known today as a cheap bourbon, was a codename for Allied military personnel carrying out fairly primitive electronic maneuvers, such as jamming enemy broadcasts. Today there is an international Association of Old Crows, boasting some 14,000 members, promoting conferences, classes, and lobbying among researchers, industry, and government in the hugely more sophisticated arena of EW, electromagnetic warfare. This seems to be a lesser known corner of the Big Picture, in which the U.S. is far and away the world’s largest arms supplier. The Old Crows are surely deep in that Washington Swamp so decried by virtuous politicians.

Enters war again: “Eating crow” is a traced to a War of 1812 incident where a British officer forced an American soldier to consume part of a crow that the Yankee had shot over the border in British territory. Whether or not the story is true, crow meat is said to taste like the dark meat of any wild bird. Roasted slowly in red wine, it has been declared delicious. On the other hand, an Australian recipe suggests simmering the bird with a stone for three hours, then draining the liquid and eating the stone.

This morning I went across town to pick up sacks of co-op-farmed vegetables to be shared with friends. Two crows were trotting around self-importantly, pretending to be supervising the operation–a fine illustration of today’s urban-agricultural interface.

Fire, Fear and Unnaming in Berkeley, Budapest, and Parnassus Heights

As the world knows, California is ablaze once again, and there is blame enough to go around–starting with Trump, our climate science denier-in-chief and crown prince of fossil fuel protection.

Despite the repeated charring of millions of acres of the Pacific northwest, as well as the planetary pandemic and social and economic collapse, we continue to engage in the pettiest local squabbles over race and gender, history and hearsay. Along with news from the so-called Cancel Culture come daily reports of moving and removing statues and statutes, un-naming and renaming schools, streets and soup kitchens.

In a rare glimmer of light from the murky swamp of identity politics, a 1936 mural on the history of medicine in California, seems likely to survive the demolition of the building that holds it.

The History of Medicine, by Bernard Zakheim in Toland auditorium, Parnassus Heights Campus, University of California, San Francisco

The mural, a fresco in a lecture hall on the Parnassus campus of the University of California, San Francisco, shows in one of its panels a Black nurse, Bridget (Biddy) Mason, ministering to a plague-stricken citizen. In this case the plague is malaria. But the point is that she is standing elbow-to-elbow with various bearded white elders of the Gold Rush state. To the right is a laboratory table where three of the hirsute gentlemen appear to be researching a vaccine or a cure. There is no sinister imperial or racist subtext to this scene’s narrative. Biddy Mason, a former slave, having worked as a midwife and healer, became known–in whatever order–as a church founder, a real estate entrepreneur, and a philanthropist. But how, in this time of racial and feminist turbulence, can this mural not be valued, and prominently displayed in the new Parnassus campus?

In 1945, my family moved to San Francisco so that my veteran father could study for an engineering degree. Meanwhile, my mother worked on Parnassus Avenue above Golden Gate Park at the medical center. My doughty little grandmother looked after me and my brother. Sometimes she walked us over to meet my mother after work, with me on my skates circling them self-importantly.

Parnassus Heights had been the site of the University of California’s first anthropology museum before it moved across the bay to Berkeley.

Tent city in Golden Gate Park after 1906 earthquake. Many sought medical help from the hospital at the Parnassus campus, visible in distance.

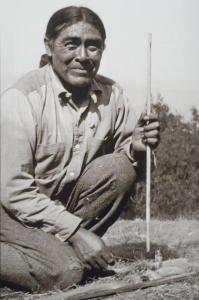

In that old museum, Ishi, the “last wild Indian in America,” brought there in 1911 by the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, spent the last five years of his life. He chipped arrowheads, sang songs, and made fire for scores of fascinated visitors to the museum. Above the museum, Ishi had a brush hut, and perhaps a cave further up the slope.

Sixty years later, my anthropologist son traced the original hideout in the mountains where Ishi had survived as last of his tribe. He describes the networks of tribal and institutional interests that emerged as he recorded the saga of the search for Ishi’s brain and the repatriation of his remains (Ishi’s Brain, Orin Starn, Norton 2004).

Fifteen years later, in a related instance of identity politics, UC-Berkeley felt obliged to establish a Building Un-naming Review Committee to accommodate our recently reawakened anti-racist ardor. Kroeber Hall and the anthropology museum’s number soon came up.

Sadly, un-naming and other symbolic changes such as renaming buildings, seldom appear to affect the substance or tenor of what happens within them. In removal of monuments and names from our shared racist past, we run the risk of confusing re-branding with reform. With repentance, perhaps, for the many thousands of California Indians killed and displaced by the time Ishi was discovered.

Whether Alfred Kroeber was truly Ishi’s friend or merely his patron has been much discussed—most recently in the charges and counter-charges in the case of the “Un-naming” of Kroeber Hall. After a hundred years the issue is still unclear. No, Kroeber was not responsible for the wholesale excavation of Indian graves and mass storage of their bones. He did write a great deal about the California Indian cultures, did testify importantly about them to the Indian Affairs Commission. But yes, he did ship off Ishi’s brain to float in a tank at the Smithsonian Institution.

Unlike un-naming, toppling or defacing a statue has at least an immediate visual effect– not to mention another alternative, which is banishment to a civic graveyard of politically superannuated statues like that in Budapest.

Last year saw the disappearance of a popular statue of Hungarian Resistance leader and anti-Soviet prime minister Imre Nagy. In a rather obvious maneuver of historic revision by the government, Nagy’s statue was shunted off to a less central location.

As yet there is no monumental statue of the current Hungarian autocrat, who presently has most cordial relations with Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, if not with most leaders of western democracies.

Here Orban appears 25 years ago, eloquently denouncing the Russian occupation–at the ceremonial reburial–of none other than Imre Nagy.

occupation–at the ceremonial reburial–of none other than Imre Nagy.

But that was then and this is now.

It’s perhaps cheering to Viktor Orban’s detractors that the Budapest Memento Museum has space to accommodate any number of rejected politicians in the near or distant future.

And Kroeber Hall may be re-named after Ishi. Of course we don’t know his real name: “Ishi” was the word for “man” in his Yana language. ∞

Hotels in Times of Trouble

Not the Majestic Hotel, but very like

Trouble at the Majestic

The year is 1919, the scene a decaying imperial spa in County Cork, Ireland. The owner of the Majestic Hotel is an Anglo-Irish aristocrat who cares more for his dogs and piglets than for the starved villagers who raid his potato patch by night. His beloved piglets are housed in the former squash court and fed yesterday’s pastries.

The Majestic Hotel figures in Trouble, a tragicomedy about the Irish rebellion against British rule–performed against a background of guerrilla attacks by the rebels and vicious reprisals by the British. The “Troubles” exploded again in 1970, the year that J.G.Farrell’s remarkable novel appeared.

PROJECT ROOMKEY

A century after the partitioning of Ireland, amid the planetary chaos of the coronavirus pandemic, California’s vacant hotels suddenly figure in a social and economic crisis of survival.

California governor Gavin Newsom, confronting the vulnerable and potentially infectious mass of 150,000 homeless in the state, has engineered an ingenious deal. Hotels and motels, most notably Motel Six, have made available for lease some 15,000 hotel rooms for housing the most fragile homeless–the aged and those with underlying health conditions.

Newsom announced Project Roomkey at a press conference in front of a Motel Six in Campbell,California. Campbell is an unremarkable Santa Clara Valley town where I went to high school, when prune orchards were just giving way to housing tracts, highways, and the garage startups that transformed the farmland suburbs into Silicon Valley.

Looking west over Silicon Valley

In the early days, Campbell, California had at least one street of “affordable housing,” inhabited by poor people, then generically called “Okies”. Gilman Avenue was a few blocks of small greyish bungalows, some with junked cars as lawn furniture. Betty the Moocher lived on Gilman. She was pallid and grimy with a plaintive, small-featured face. During lunch hour she would stand nearby, gazing silently at your sandwich. Sometimes we would give her something. It never occurred to me that she could actually have been hungry, though there were no free lunch programs then.

One of those Gilman bungalows is for sale right now as a “vintage” fixer-upper, for $1,220,000. Down half a million from its earlier listing. Most people cannot now afford any sort of home in California, but there are more free lunch programs. Just no housing.

One of those Gilman bungalows is for sale right now as a “vintage” fixer-upper, for $1,220,000. Down half a million from its earlier listing. Most people cannot now afford any sort of home in California, but there are more free lunch programs. Just no housing.

Given the continuing pandemic lockdown, Project Roomkey hotel rooms would have been vacant anyway–a seemingly perfect solution, with FEMA ready to pay 75% of the costs. But two weeks ago only some 4,000 of the 15K available rooms were occupied. Tidy charts showed how many rooms had been leased for the project, how many were being prepared for occupancy, and the relatively few which were actually occupied.

It is not a simple process. The first challenge is the vetting of would-be occupants, by experienced social workers already overstretched by the Covid crisis. Applicants range from the responsible but roofless and medically fragile to lifelong addicts who may trash their rooms if not regularly supplied with their drugs. Medical records and background checks are needed. Staffing has to be arranged to provide food, housecleaning, medical help–and security.

Several counties have already signed onto Project Roomkey. But a number of southern California townships have rejected any use of their local hotels as homeless housing, either temporary or permanent. And anecdotal reports from some of the occupied lodgings are not good. Social distancing, along with housekeeping and private property, are unfamiliar concepts for many formerly homeless folks.

California has the fifth largest economy in the world, one of the highest costs of living in this country, and the largest number of homeless of any state. Some see this as flagrant evidence of a failed government–the inability to provide for the welfare of its least able citizens. Newsom, as governor, and earlier as mayor of San Francisco, took on homelessness as his central issue. There was the controversial Care Not Cash, which reduced cash support and increased shelter and social services. Now there is Project Roomkey.

Here in my present hometown of Berkeley, 40 homeless have moved into two Oakland hotels that are part of Project Roomkey. Each room is $186 per day, to be 75% reimbursed by FEMA. For whatever reason, Berkeley jokes aside, these are not Motel Six rooms like those claimed by other counties, which normally rent for $76 per night. Meanwhile the proposal for 16 stories of housing to be built at People’s Park brings out opponents pointing to its 50-year history as a political symbol and a refuge for the homeless.

Newsom and his allies would like to see Project Roomkey succeed and extend beyond the pandemic. This cannot happen without aligning funds from state, local, and federal sources. And so far, even money has not proven to be the answer. Homelessness was a serious problem in California long before COVID-19, and will doubtless increase afterwards, given the economic devastation of the work stoppage as well as earlier problems with local zoning and construction workers’ unions.

Bond issues for building affordable housing have been passed and then failed dismally to address the need. In California it costs $450K to construct one no-frills unit of subsidized low-cost housing. This is based on rising costs of labor and material and the expensive delays between securing funding and local approval of the project and the site. Given the cost of new construction, adapting ready-made housing seems a rational solution to the very immediate needs of California’s 150K homeless.

Some say that this apparent emergency will shrink back into perspective once our society returns to normal. Others point out that “normal” has included indifference not just to homeless encampments under our clogged freeways, but to the climate crisis, to enormous income inequality, to mass shootings, and to the continuing partitioning of our electorate that gave us Donald Trump. ∞

Magnolia Street and the Vienna Model

This story cut a path between impeachment fatigue and the coronavirus right into the California governor’s office and the international media. Four homeless mothers moved with their children into an abandoned house on Magnolia Street in Oakland, California. They cleaned it, connected the utilities, decorated for the holidays. Before long, of course, the owner, a southern California real estate corporation, threatened to evict them. Although public support was growing, a local court ruled against the mothers. County sheriff’s deputies in riot gear promptly staged a dawn raid on the house, complete with drones, tanks, robots, and AR-15’s. The sheriff declared himself well-satisfied with the timing and efficiency of the operation.

Meanwhile, sympathy for the mothers was feeding outrage against real estate speculators profiting at the expense of local tenants and the homeless. Some 6,000 vacant houses have been tallied in the city, while homeless encampments are everywhere–under freeway overpasses, on sidewalk strips, in public parks, at busy intersections.

As homelessness spreads globally, it overlaps with the migration crisis and gross income gaps, euphemized as inequality. Today’s Germany, with its generous welfare provisions, attracts not only masses of refugees, but investors looking to take advantage of both the housing shortage and government subsidies of skyrocketing rents. The German government spends about 4 billion euros on public housing projects and subsidies each year, and covers some 15 billion more in rent for social welfare recipients. One economist noted drily that the government program could be described as an “economic stimulus package” for property-owning landlords. In Berlin protesters have succeeded in extracting a five-year rent freeze from the government. Landlords and developers say they will simply move their operations to other German cities. Meanwhile, another economist estimated that given the current rate of construction, it would take another 185 years for Germany to provide housing for those in need.

The VIENNA Model

Just across the border in Austria, Vienna is often rated the most livable city in the world. 60% of the population live in social housing, mostly by preference. Large, well-designed housing estates are built and managed to attract and maintain tenants with a broad spectrum of income. The daughter of a former president was on a wait list for one of the most desirable projects.

When I was in Vienna as a student, three of us shared a large bedroom in the apartment of an impoverished baron and his family, just a block from the State Opera House. At the end of the Habsburg empire, not much had been left for the Austrian aristocracy. The staff of our institute included an overworked countess, and our landlord, the baron, could not have been happy to rent part of his home to a gaggle of American girls. Our room had high ceilings and tall, glass-windowed doors that rattled when the Frau came with our breakfast tray, laden with milchkaffee and precisely measured tiles of butter with just enough apricot jam for each of the fat kaiser rolls. After all, the Frau had managed to feed her family through the postwar shortages.

Much earlier, after the First World War, having exiled the troublesome emperor, the new Austrian republic did not sell off land to private bidders, but created a series of housing estates. Under the social democratic government, from 1919 to 1934, in so-called Red Vienna, the projects and their fittings were designed by world-famous artists and architects. And after the Second World War, the Austrian government resumed building and restoration. In today’s Vienna, residents live in some 420,000 apartments in assorted social housing projects owned and managed either by the government or by selected nonprofits.

In America, housing projects are often poorly-maintained and crime-ridden, a form of ghettoization that people want to escape. In Vienna the projects (Gemeindegebau) are where people want to live. But this network is expensive to build and maintain, and given the influx of asylum seekers needing housing, the city’s housing blueprint may be changing. While all profits from rents are ploughed back into new construction, the system relies on heavy taxation that Americans have historically resisted.

Wedgewood, Inc. was founded in 1985 in Redondo Beach, California. Its corporate headquarters inhabits some 50,000 square feet in this pleasant beach community. The company describes itself as “an integrated network of companies concentrating on real estate opportunities.”

Redondo Beach was until recently also the corporate home of Northrop Grumman, the second-largest defense contractor in the USA. Northrop’s highly diversified operations included in 2003 a $48 million contract to train the Iraqi army, and more recently, the design of the Global Hawk drone downed last year by Iran. The US has only three remaining of this $200 million aircraft, but replacement should be simple given the $718 billion budgeted for defense in 2020. This same budget apportions $44.1 billion for Housing, which is a fairly clear illustration of national priorities.

Northrop recently moved its headquarters to Washington D.C. to be near its main client. But Wedgewood, Inc.remains in Redondo Beach–as does a great deal of discretionary income. Real estate investments reap historically high profits. The current ROI (Return on Investment) for so-called fix and flip investments often exceed 100% of the original investment, although the current ROI (Return On Investment) clocks in at a relatively low 40%.

Wedgewood owns around 120 other Bay Area properties besides 2628 Magnolia Street. In the agreement negotiated by Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf and Governor Gavin Newsom’s office, Wedgewood agreed to sell the Magnolia Street house to the Oakland Community Land Trust–and to offer their other properties as well to the tenants before putting them on the open market. This “right of first refusal” has been a successful principle of tenant activism in other progressive cities. This is a serious victory for the local branch of housing activists in the Alliance for Community Empowerment, and a cautionary development for real estate speculators.

Wedgewood does not own the Oakland apartment complexes where residents have been withholding rent because of poor maintenance, and even organizing to buy the building. These tenants will welcome the breaking news that the Alameda County district attorney’s office has withdrawn all charges against the Moms4Housing collective and their supporters.