Yes, a splashy opener— Some of us can remember when the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude was as often ridiculed as respected. Now we have slouched past the centennial of Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, when he introduced a piece of shapely plumbing as a work of art called Fountain, and “signed” by R. Mutt, its manufacturer. … Continue reading

Early Postcards from Aleppo, Belated Cease-fires from Munich, and Picking Up the Pieces

And more recently…… Last week from Munich came a triumphant announcement by foreign secretaries Kerry and Lavrov of major humanitarian interventions in Syria, to be followed in a week by a cease-fire. Celebration was muted, and within hours the news was qualified, deprecated, and disparaged by almost everyone not involved in the negotiations, and … Continue reading

Looting and Decapitation through the Ages

In yesterday’s museums, few visitors knew or cared whether an emperor’s polished marble likeness or the graceful body of a goddess had once been goods for barter in some tomb robber’s grimy hoard. Now the end of colonial empires and the fevered growth of nationalism favor returning looted art to its place of origin. … Continue reading

Syria, All of a Sudden

At the end of September 2015, in the fifth year of the relentlessly ruinous Syrian civil war, all the world has been forced to take account of some two million refugees from that conflict, along with those from other ruined countries, seeking asylum in Western Europe–or as … Continue reading

Ritually in August, Europeans repair to their mountains or beaches while tourists throng their cities. But by early July, the 2015 Venice Biennale, already darkly apocalyptic, was also featuring the 110-degree afternoons of global warming. Completely flattened, we fled to the Dolomites, whose snowy peaks are still visible from Venice on very clear days.

The Dolomites are seen in the background of paintings by Venetian masters, and by northern painters whose horizons lacked mountains.

Titian, raised in the Dolomites, painted a portrait of Catarina Cornaro, queen of Cyprus (and, some say, of Armenia). Catarina was forced to abdicate and cede her country to the Republic of Venice. She was allowed to keep her title and given a castled court in Asolo, safely removed from the circles of power. Titian decks her out in the Turkish-style brocade coat which complimented the generous curves of so many Venetian ladies. Any soprano in Donizetti’s Caterina Cornaro would be likely to wear it, but since the opera was booed at its 1844 opening in Naples, it has seldom been staged.

A pair of smoky-skinned youths, toting racks of colored beads, took a table next to us in a café next to the bus stop in Corvara. Here we were, merely escaping a heat wave. How had they made their way so far up into these mountains? Had it occurred to them that a resort town might have less competition and wealthier customers than a crowded city? What to make of the lush green valleys and flowing waterfalls of this alpine paradise? Probably they were en route to Germany, more or less as the crow flies—or according to a Google map.

Germany we are told, expects to receive 800,000 refugees next year.

Meanwhile, the presidents of the Veneto and Lombardy had just ordered towns in their regions to stop accepting migrants altogether. Six thousand refugees had been rescued from the Mediterranean in the previous weekend, and many thousands more waited to embark from Libya and Turkey. Renzi and his government in Rome counseled Italians to be humane and accept the migrants across the board.

No way, said Luca Zaia, regional president of the Veneto.The situation “is like a bomb ready to go off.” Roberto Maroni, president of Lombardy and former leader of the conservative Lega Nord, threatened to cut the funding of any compassionate municipalities who encouraged refugees to settle.

One morning we took a local bus from Corvara that wound through the mountains toward a small town known as Ortisei in Italian, St. Ulrich in German, and Urtijei in Ladin, an ancient alpine survival of Latin, spoken by most of the townspeople. (Place signs are in all three languages.)

Climbing the steep main street of Ortisei, we came upon a very large heap of white plaster bananas, not far from a cannon made of wood. Public art, we noted shrewdly. The artists, we read on a placard, intended an ironic message about climate change with reference to the past winter in Ortisei, when the only snow available to skiers came from strategically placed “snow guns”

Further on, the street opened onto a large , quite affecting monument by Armin Grunt (umlaut u) depicting the miseries of migration.

Woodworking was and remains the major art and craft in these forested mountains. But tourism became the mainstay of their economy in the last century, increasing after the famous Winter Olympics of 1956 took place in Cortina d’Ampezzo.

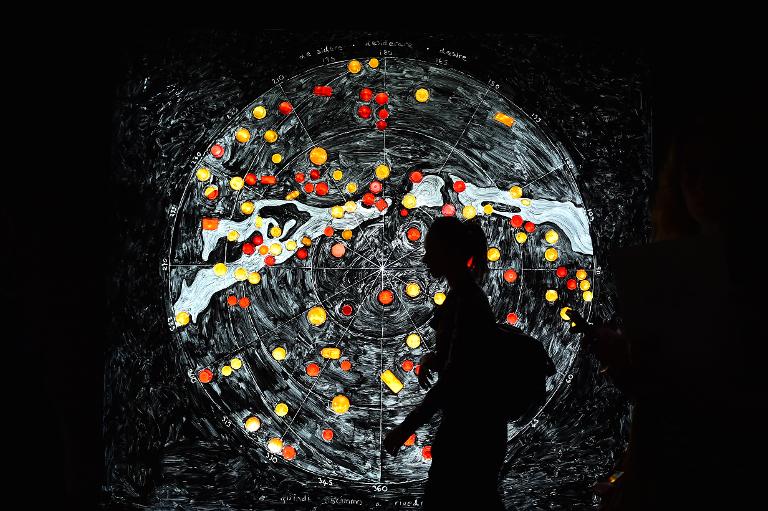

This year, the 56th Venice Biennale, the world’s most famous art event, manages to condemn not only climate change, capitalist exploitation of labor and industrial pollution, but global starvation, planetary degradation, and the arms trade—in just two gulps, one at the Arsenale site and the other at the Giardini.

Actually, the Golden Lion prize for the best national exhibit went to Armenia, outliers on the monastery island of San Lazzaro, marking the centennial of their genocide and diaspora. We happened to go to the island on a Sunday afternoon, and found ourselves caught in a line moving relentlessly into the church for the Orthodox mass, nearly two hours long.

It is sometimes said that art art can take you anywhere, and this year’s Biennale does compel you to visit unlikely places, from the assembly line of a cultivated pearl factory to gay brothels in Chile. Many of the heavily didactic exhibits are of videos and photos, with displays of significant documents, such as international agreements repeatedly dishonored, or newspaper clips with false information, or contracts you make with yourself.

The Australian Fiona Hall is more direct.

Her imaginative work fills the whole pavilion and includes a 3-D map of the southern Mediterranean scattered with tiny figures, indicating the migrants who drowned in one week between Africa and Italy.

Other artworks have related messages.

Although there is plenty of irony, subtlety and ambivalence are not qualities that many of these artists value. They are desperately concerned for the future of their own countries and the world at large. Still, their Biennale appearances are financed by capitalist networks that certainly include artists’ galleries, and most of the work, in case you were wondering, is for sale.

Alongside the galleries in the Dolomites that show woodworking artists, are regional museums focusing on alpinism (mountaineering) and local history, including that of the so-called White War.

At almost eleven thousand feet, Marmolada is one of the highest peaks in the Dolomites. During World War I, as one military front shifted into South Tyrol, Austrian troops tunneled into Marmolada’s northern glacier and the Italians into its rocky southern face. Somehow they made it possible–building roads, dormitories, and gun emplacements–f0r thousands of soldiers to exist, and to fight, in the brutal cold at altitudes where only mountaineers and shepherds had ever ventured.

A hundred years later, in our warming world, the icy slopes are melting to reveal grim relics—soldiers’ corpses and rusted armaments. Some 150,000 men died in the White War, only a third of them in battle, the majority from avalanches, frostbite, and other effects of the extreme cold. Likely, in warmer decades to come, spring skiers will continue to make grisly discoveries in the Dolomites.

Partly as a result of the White War, in 1919 South Tyrol was given to Italy, and those 150,000 Austrian and Italian soldiers died in a struggle over national/imperial hegemony that their sons and grandsons have mostly disavowed. In the mountains, what they worry about now is climate change, whether they will have snow for the ski crowds, or whether they will have to depend on the snow cannons. Down on the flatlands, they are worried about new waves of migrants, most of whom have paid their last thousand euros to find asylum or at least work and food in the West.

Few saw just how fragile and flammable the Middle East would prove, how quickly the drying up of the Sahara, the continuation of brutal governments, the series of drought years, and the internal wars would displace millions. The tens of thousands of refugees spilling into Germany, Italy, and France from the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa are economic and sometimes political refugees. Their lives and their families’ lives are on the line when the cost of passage on a leaky raft or rusty ship. They’re fleeing, most often they know not where.

In America the flaming issue of next year’s presidential election has become immigration, from Mexico. In Hungary a far-right government constructs a fence to stop the influx of refugees arriving from Serbia, Macedonia, Greece. A Hungarian friend says that the brutally anti-migrant stance of his government is secretly admired by leaders of the European union. Whatever the case, Germany is in ever in a bind to show that its past inhumanity was an aberration. But Germany by itself cannot absorb these millions.

A year ago I tried to chart some of the tragedy of Syria since the civil war began. The latest chapters include demolition of another temple in Palmyra, and the changing route of Syrian refugees: they are now travelling north to the Arctic Circle and heading for the Norwegian border, to the little town of Kirkenes, 2500 miles from Damascus. Norway has nothing to prove about its humanitarian history, and welcomes them.

“On Prague,” from Threepenny Review’s new anthology

[Winter 1991] From Prague friends write in their uneven English, always better than my clubfooted Czech, “Here we live now a little in a madhouse. I hope only that we shall be saved before too great idiocy. To teach and to learn the democracy is the most hard work in the world,” reports one, … Continue reading

Dinner in a Time of Drought

Given a bootless succession of balmy, deep blue evenings in drought-stricken California, we invited some friends for an al fresco dinner—two Italians, one Romanian, a Scot, a Moroccan, and three of their boys. The transcontinental jumble only occurred to me later, when I was lying awake, regretting my clumsy vinous Italian, and the surplus of food I usually prepare, especially when there are vegetarians.

S. and I were in the kitchen sorting the berries she had brought. She said that her husband had just returned from a long stay in Fez, where he had to look after his sick mother and two eccentric sisters. This reminded me of Abu Hani, our wise, kind driver in the months before Syria’s war; his wife and two unmarried daughters had seemed shielded and restricted in the Muslim manner. Since he had fled Safed in 1948 to settle in the Palestinian quarter of Damascus, now devastated, probably his family are now Syrian refugees. There must be a term for repeat (recidivist?) refugees, like the Armenians, just marking their first century of diaspora.

Nina Khatchadourian’s video, called, cunningly, “Armenities,” is a telling exploration of her parents’ layered languages learned in serial homelands. “Armenities” will be at the 2015 Venice Biennale—in the island monastery of San Lazzaro, where lepers were the original refugees.

The bay fog had blown in while R was grilling sausages, and suddenly it was cold and damp, drought or not–the downside of our famous marine climate. Everyone helped shift all the food into the kitchen, filled their plates and reconfigured at the dining table. Someone sought common ground, so to speak, talking sports with the three boys.

That’s when I turned to our Moroccan friend. F. speaks softly with a heavy French-Moroccan accent, but I think that he told me that his father left school at age seven to help support the family, and eventually became a successful merchant who sent nine children to college—the middle one, our friend, to Harvard. Writers admired by F. include Borges, Calvino, and Marquez; he is now writing stories himself, based on centuries-old tales that he had found in the souk in Fez. He has a shy flash of a smile, winsomely conspiratorial.

Early in this century, R and I flew to North Africa, after a conference in Florence, where R talked about the Laocoon (and I nursed a fractured wrist). We went to Morocco, which was for us entirely otherwhere. There was a bright, almost hallucinogenic light across the sandy plain, not unlike the light we have now in drought-parched California. Along the highway was a sparse strewing of people on foot and pieces of litter, mostly plastic. William Kentridge makes dark kinetic profiles of people who might have been moving along such a highway in South Africa.

In Rabat, after dining on a fine pastilla, with music, we wandered off in the moonlight toward a mysterious truncated tower sharing a site with hundreds of stubby marble columns. We didn’t find out what it was until the next day.

Hassan Tower, minaret and mosque, columns left unfinished in 1199.

Sad to say, returning to our hotel, we lost our way and were maliciously re-directed in loops through the city. Next morning, on the train to Fez we shared a compartment with a Moroccan lawyer who expressed confidence that the new boy monarch would be guided by his enlightened sister, within the limits of sharia law, of course.

When F. had mentioned the old story collections he had found in the souk, I had to tell him about our son’s graduate student, a Turkish Kurd, who was cashiered at the airport in Yerevan for stowing old books from the market in his baggage. Our son had bought his first business suit and travelled to Armenia to spring his student.

After more wine, and the stealthy withdrawal of the kids into the living room with their pads and phones, new topics arose at the table. Nothing heavy: for example, where had the motley couples first met? One pair in Grenoble; another in London; another in L.A.; and (much earlier), R and I in Vienna.

Vienna in 1958 was still what you may remember as the shadowy postwar background of “The Third Man”. I lived with the family of an impoverished old baron in a palace on a corner near the Opera. Each morning, the baron’s young frau measured out very carefully the butter and jam for our breakfast kaiser rolls. My roommate, who befriended her, said that the frau’s true love had been killed in the war. One day the baron called me quite literally on the carpet, in the dark, high-ceilinged hall, to scold me for blocking the street entrance late at night while necking with R.

Italy was also grimly postwar when we first saw it. On the other hand, our caro amico M. says that he doesn’t want to live in today’s Italy, which is not the country that he knew growing up. I lived in Florence during some of those years, but Italy seems to me still much like itself, each region colorful and/or and corrupt in its own way, Florence possibly less than most. (Matteo Renzi, the youngest prime minister ever, was mayor of Florence and advocates reforms that alienate both the left and the right.) As for me, I am now immersed, so to speak, in Venice, where corruption is endemic and close to entertaining.

What M. loves is California. After a detour of a few years on the East Coast, he returned to California just in time for the drought. While the rest of us were saving shower water to dribble on our flowerbeds, M. planted exotic succulents in large pots–also a very good plan since he needs to spend a great deal of time elsewhere, in St. Petersburg, Russia, and Reno, Nevada, for example.

M. had brought a big raspberry tart, which I put on the table, with S’s berries. Having just finished one of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, I wondered what S. thought of her. She didn’t know her work, which surprised me, although her own field is Middle Eastern culture. I thought that she had said earlier that she was from Rome, but when I brought out my copy of L’Amica Geniale, she pointed out, in the cover photograph of the bay of Naples, the very school she had attended as a girl.

Why isn’t S. considered a refugee, from Naples (or Rome)? Is M. a Tuscan exile? It’s all in the element of choice, I suppose, which usually comes with education and a dependable income.

The Armenian genocide was the first of the twentieth century. In 1915 Dr. Clarence Ussher, a medical missionary.working in the Van Province, bore witness to the massacres of the Ottoman Turks. Dr. Ussher was ancestor of a valued friend, the remarkable writer Nicholson Baker, a committed pacifist and author of the revisionist war history, Human Smoke.

An important center of Armenian culture is the Venetian island of San Lazzaro, which was resettled in 1717 by a dozen Armenian Catholic monks who arrived in Venice from Morea in the Peloponnesus, following the Ottoman invasion. They renovated the church of St. Lazarus and constructed gardens, a seminary, and other buildings. Napoleon left them alone after he conquered the Venetian Republic in 1797. Some say this was because of an important Armenian member of Napoleon’s staff.

Little-known fact: Lord Byron lived on San Lazzaro from late 1816 to early 1817. In short order, he seems to have learned enough Armenian to translate passages from classical Armenian into English, and even to co-author grammars of English and Armenian.

Aside from tending their huge library, the Armenian monks produce 5,000 jars of rose petal jam per annum, a number of them eaten by the monks themselves, and the others sold in the San Lazzaro gift shoppe.

In the world outside the island, the questions of Armenian genocide and property restitution continue fraught. Solutions have been suggested: Armenian churches and monasteries currently used as storage facilities by the armed forces could be handed back to the Armenians. Beyond that, collective compensation might be modeled on German compensation to Jews. Turkey could also take in Armenian refugees from Syria and Iraq, could offer Turkish citizenship to Armenians who want it, could remove the names of perpetrators of the genocide from Turkish streets signs and places.

Meanwhile, Kim Kardashian, famous for being famous, and by far the best known Armenian in the world, says, “I am saddened that still 100 years later not everyone has recognized that 1.5 million people were murdered. But proud of the fact that I see change and am happy many people have started to recognize this genocide!”

Here she is with her husband, rapper Kanye West, one of Time‘s 100 most influential men in the world.

In Syria as well, one of the main rebel groups is welcoming the attention from Kardashian.“We are glad Kim Kardashian is taking an interest in this issue, as we too are concerned about extremist groups’ persecution of minorities,” Khalid Saleh, a spokesman for the Syrian National Coalition, told The Daily Beast. “The Free Syrian Army has put out a statement committed to protecting of citizens of Armenian descent and to maintaining the integrity of their religious sites…”

Question: shouldn’t Kardashian be coordinating with Angelina Jolie, who has been earnestly trying to raise international consciousness about the Syrian crisis for several years?

Some doubt that Kardashian could find Armenia or Syria on a map, but this is petty carping. How often can beauty could speak to power and be heard? If only I had brought this question to the dinner table.

From Raqqa to Istanbul, and counting

How long would it take an Islamic State purification patrol to reach Istanbul? From Raqqa, Syria, the current Daesh capital, it’s only 870 miles, a fifteen-hour drive northwest through Aleppo and Adana, with possible traffic delays around Ankara. However, road conditions on the Syrian leg may have deteriorated recently, and then you can’t always … Continue reading

Doomsday Clock and Related Last Things

The very first apocalyptic clock was on the cover of the 1947 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, established by men who regretted their role in the catastrophic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. With climate crises and the current conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, the Last Midnight looms. Only 89 seconds between No Kings Day … Continue reading